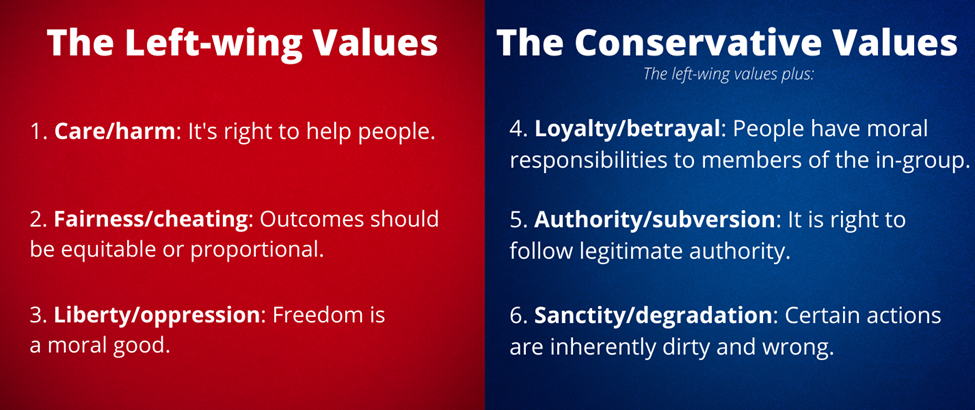

As past Values Added articles have explained, there are six different values that people hold, and these values are key to understanding our worldviews:

Although everyone holds all six values to some degree, people experience them in different ways. Some people believe that the care/harm value is the most important, but also feel the pull of the fairness/cheating and the liberty/oppression values. Others believe that all six are equally valuable. This is normal. In fact, our moral views can be roughly predicted by our membership in political groups. For example, libertarians tend to weigh the liberty/oppression value heavily, but care little for the loyalty/betrayal value. Although this is a fair generalization, it’s somewhat incorrect. Within every group, there remains significant diversity, as everyone has their own personal weighting of values as well.

Read more