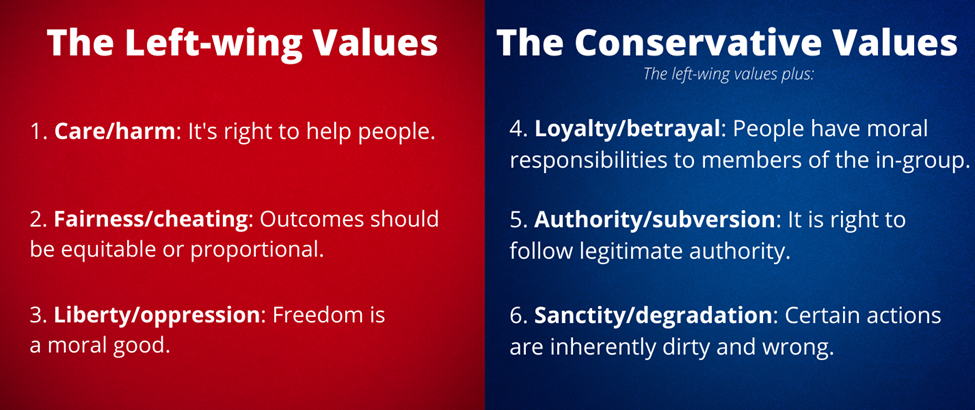

As past Values Added articles have explained, there are six different values that people hold, and these values are key to understanding our worldviews:

Although everyone holds all six values to some degree, people experience them in different ways. Some people believe that the care/harm value is the most important, but also feel the pull of the fairness/cheating and the liberty/oppression values. Others believe that all six are equally valuable. This is normal. In fact, our moral views can be roughly predicted by our membership in political groups. For example, libertarians tend to weigh the liberty/oppression value heavily, but care little for the loyalty/betrayal value. Although this is a fair generalization, it’s somewhat incorrect. Within every group, there remains significant diversity, as everyone has their own personal weighting of values as well.

To illustrate the values set of an individual, I use the term a moral portrait. You can learn your own moral portrait by completing this questionnaire managed by leading scientists in moral psychology. This is the standard way to assess someone’s moral views: ask them a bunch of questions and draw conclusions from their answers.

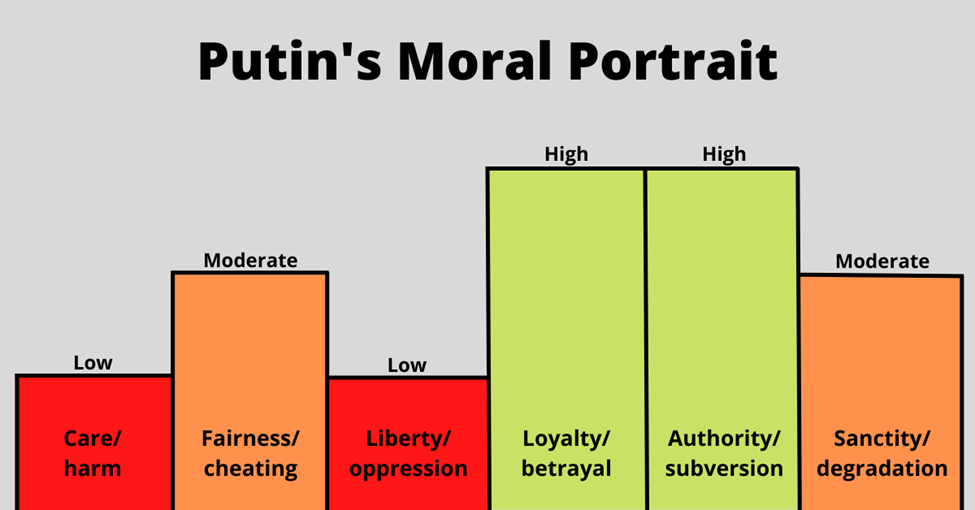

Although this methodology is solid, it requires the active participation of the subject under study. Unfortunately, the most influential people in the world, world leaders, are unlikely to fill in a survey, and it’s their moral views that drive international events. To fill this gap, I attempted last week to develop a moral portrait of Vladimir Putin based on open-source evidence. Given that the President of Russia has well documented views, I believe that it is possible to build a broadly accurate illustration of his values, which could provide critical insights to responding to his behaviour. Here were the results:

In short, Putin appears to be most driven by the loyalty/betrayal and the authority/subversion values. The sanctity/degradation and the fairness/cheating values are also important, and they could help explain certain decisions. Bringing up the rear are the care/harm and liberty/oppression values, which are unlikely to drive his behaviour (although they still could in some situations; no one is completely immune to any value).

With this moral portrait in hand, we can derive a few important insights that could inform our response to Russian aggression in Ukraine and beyond. I’ll focus on the loyalty/betrayal value, as it is one of the most important to Putin:

1. Take stated concerns about the rights of Russians in Ukraine seriously.

One of Putin’s stated goals in his war is the protection of Russian speakers in eastern Ukraine. He raises it directly in his article On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians, arguing that the Ukrainian government is pushing Russians who live in Ukraine to accept a “forced change of identity”. According to Putin, this “forced assimilation” has several prongs. First, the Russian language is under attack, particularly in the education system. Pointing to several laws that have reduced the role of the Russian language in schools and in civil society, Putin claims that the Ukrainian government is forcing Russian speakers to use Ukrainian in everyday life, weakening the ties of ethnic Russians to their ethnic nation-state.

Second, the Ukrainian government passed a law on “indigenous peoples”, which granted special legal protections to certain national groups that reside within Ukraine’s borders, such as the Crimean Tatars. These groups received the right to education in their native language, protection of their historic heritage, the establishment of their own media outlets, and the creation of representative bodies to defend their interests. Russians were not granted these protections, despite pressure from the Russian government and the pro-Russia party in the Ukrainian parliament. According to Putin, this law has furthered the forceful assimilation of Russians.

Third, Putin argues that the Ukrainian government fabricated an ecclesiastical break between the Ukrainian and the Russian Orthodox churches. Worse still, Putin alleges that the Ukrainian government encouraged violence against the Russian Orthodox Church, including “the seizure of churches, the beating of priests and monks.” To Putin, this was done exclusively for political reasons against the wishes of the Ukrainian population.

Putin has concluded that these events, plus baseless accusations of imminent mass killings, have risen to the level of genocide that required a military response from the Russian government. The language is remarkably emotive and forceful, and yet most commentators either underplay or totally omit it. They say the real explanation for why Putin invaded lies elsewhere. It could be that NATO expansion threatens Russian security, Putin must protect his kleptocratic regime from an alternative democratic model, or he just wants to rebuild the Soviet Union. These are all valid explanations that worthy of discussion and consideration. However, these interpretations reduce Russian grievances about language and religion to red herrings that are simply meant to provide a domestic audience with a righteous cause to justify an illegal war. To many commentators, Putin couldn’t possibly believe the ridiculous notion that genocide was occurring in Eastern Ukraine, so the only reasonable explanation is that he was giving one justification, while actually acting on another.

I disagree. Putin could believe what he’s saying, and values analysis suggests he probably does. Russian leaders who are high in the loyalty/betrayal would be expected to have a strong negative reaction to any effort to discourage the use of their language in civil society. Such leaders would also feel a responsibility to protect ethnic Russians in neighbouring countries. To a nationalist, efforts to restrict the use of Russian aren’t pragmatic compromises or justified political decisions; they’re attacks on the Russian identity.

Canadians should know how important language and identity can be. The ongoing debate in Quebec over Bill 96, a popular effort to further protect the French language, has become acrimonious. It’s been suggested that it would make anglophones “second-class citizens” and that it is a “clear violation of international human rights law”. Even the term genocide has been dropped. And that’s in Canada, a wealthy, multicultural, and broadly egalitarian country. Even here, linguistic and cultural differences between French and English Canada have historically been extremely tense (they’ve even led to murder and terrorism). But no serious commentator would say that Franco- or Anglo-nationalists in Quebec are lying when they express the belief that their way of life is under threat, or that their concerns are just a smokescreen to hide some other underlying interest.

Why is it, then, that Putin receives a different treatment? To be clear: I am not suggesting that genocide was occurring in Ukraine or that Putin’s position is justified. I’m only suggesting that his position is honestly held. A leader who strongly feels the loyalty/betrayal value could interpret efforts to limit the use of Russian in Ukrainian civil society as genocidal in form or intent.

This interpretation of Putin’s worldview opens an important opportunity: offering meaningful legal protections for ethnic Russians in Ukraine is a real concession that could make a difference in negotiations, because it addresses a genuine concern. Would such concessions form the basis of a deal right now? It’s doubtful, as recent events have made any form of agreement extremely difficult. But it could help shape an off-ramp for the Russian government, a way to claim victory and go home. In short, Russian grievances in eastern Ukraine are likely important to Putin in exactly the way that he has expressed them, so it is vital not to downplay their significance.

2. Don’t denigrate the Russian nation.

Just don’t do it. World leaders have fallen into this trap before. In 2014, Barack Obama, an otherwise measured statesman, said that “Russia is a regional power that is threatening some of its immediate neighbours, not out of strength but out of weakness.” Not to be outdone, the late Senator John McCain called Russia “a gas station masquerading as a country.”

Obviously, dismissing a country as second tier would worsen relations with almost any world leader, but this is particularly true when dealing with leaders high in the loyalty/betrayal value. The emotional impact of such statements is more significant, and it can meaningfully alter their decision-making (usually making it more aggressive, as if to prove the insults wrong and defend their country). Faced with similar slurs, Putin is more likely to double down than to back off.

The recent history of Russia likely has strengthened the importance of the loyalty/betrayal value. Although the Russian Empire of the 1800s and the Soviet Union were unquestionably great power nations, the collapse of the Communist Bloc and the subsequent decade of economic, political, and social chaos were devastating to Russian pride. Ever since Putin came to power, one of the Kremlin’s primary foreign policy objectives has been to regain its status as a great power. This feeling of humiliation and ‘imposter syndrome’ operates not only within Moscow’s political elite – including Putin and his associates, who were young adults at the time and have internalized a sense of injustice and disrespect at the hands of other nations – but also among the Russian population at large. These events have served to make the loyalty/betrayal value more central to Putin.

This can be difficult for Canadians to understand because we aren’t a society built on the loyalty/betrayal value. Sure, we wear the red-and-white on Canada Day, but any Canadian who has been in the southern U.S. during the Fourth of July knows the difference between our society and a highly nationalistic one. In international affairs, Canadians are happy to downplay our importance by calling ourselves a middle power like it’s a badge of honour, despite having the eighth largest economy in the world, a significant population, membership in many powerful security and trade organisations, and a vital geostrategic position in a warming world. If it were important for Canada to have greater prestige on the international stage, and Canadians were willing to make the necessary military and foreign aid investments that such a standing requires, we could probably upgrade our position in the world. However, Canadians don’t appear to care about our standing in international power politics, in part because the loyalty/betrayal value is not a critical factor in the Canadian national identity.

But this isn’t true everywhere. Certainly, it’s not true for many Russians – or for Putin in particular – who believe that Russia is a great power that is routinely disrespected and ignored by other countries. This worldview significantly impacts how perceived insults affect negotiators’ ability to reach agreements. Although Canada’s leadership was able to swallow the numerous insults that Donald Trump threw at us and work with him, Putin is far less able or willing to stomach similar slights. And since denigrating the Russian nation brings few benefits to the West, it’s best to cease and desist.

In fact, leaders could go one step further and praise the Russian nation when appropriate. This would resonate with Putin’s loyalty/betrayal value, and potentially make negotiations easier. Obviously, I’m not suggesting that Western leaders should fall on their knees in adoration for Russia, especially in the current circumstances. However, there are a few themes, such as Russians’ significant contributions to science and the arts, that could be added to communications products.

For example, on March 26, 2022, President Biden gave a speech in Warsaw on the conflict. Yes, THAT speech; the one where he made one off-the-cuff remark that dominated the American news cycle for a week (“For God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power”). Gaffes aside, the speech itself was fine. Biden used an old Cold War trick in which a distinction is made between the Russian government and the Russian people, allowing the U.S.’s condemnation to be restricted to the regime rather than the nation. This is a wise communications strategy.

However, values analysis would recommend that the spokespeople for the American government spend more time discussing the virtues of the Russian nation, rather than just distinguish between eh nation and the leadership. Biden’s speech instead focused on the damage that the war was inflicting on Ukraine:

I refuse to believe that [Russians] welcome the killing of innocent children and grandparents or that you accept hospitals, schools, maternity wards that, for God’s sake, are being pummeled with Russian missiles and bombs; or cities being surrounded so that civilians cannot flee; supplies cut off and attempting to starve Ukrainians into submission.

Millions of families are being driven from their homes, including half of all Ukraine’s children. These are not the actions of a great nation.

This would be an excellent opportunity to speak further to Russian pride. Mention Tchaikovsky, Tolstoy, Mendeleev, and Gagarin. Lay out some of their achievements to prove the case that Russia is a great nation indeed. This language would resonate with the loyalty/betrayal value, one that is extremely important to Putin – and many other pro-war Russians.

As the speech was written, Biden only drew upon the care/harm value, pointing out how many thousands of people have been harmed by the Russian invasion. But Putin doesn’t feel the care/harm value particularly strongly, so it’s unlikely to be an effective rhetorical strategy. As well, those Russians who do feel the care/harm value are probably already opposed the war. If that’s the case, then who is this speech intended to persuade?

In contrast, Boris Johnson got the idea in a New York Times op-ed from March 6, 2022:

We have no hostility toward the Russian people, and we have no desire to impugn a great nation and a world power.

More of this would be helpful.

3. Deterrence by retaliation would be less effective than deterrence by denial

Unfortunately, the final important insight is also the most jargon-y, so allow me to parse this sentence for readers. Deterrence is aimed at preventing another actor from taking some sort of (usually violent) action by altering their cost-benefit calculations. The idea is that world leaders only act when they believe that the benefits will outweigh the costs. So, if their opponents can put their finger on the scales, either by increasing costs or reducing prospective benefits, the aggressor may prefer to do nothing.

The tools of deterrence come in two flavours: deterrence by punishment is focused on increasing the costs of taking an action, usually by threatening a tit-for-tat response, such as devastating sanctions or nuclear escalation. This is the underpinning logic of mutually assured destruction; sure, you’ll kill me, but you’ll die too. Is that really a win?

The second flavour, deterrence by denial, works by reducing the benefits of taking an action or making it unfeasible or unlikely to succeed. This could include target hardening (e.g. building nuclear bunkers) or increasing the strength of local military forces. The logic is thus: if an action is less likely to bring significant benefits, then the cost-benefit calculation deteriorates, and action becomes less attractive.

Now, I obviously have gripes about how clean and rational models of deterrence are, because the cost-benefit calculation is ultimately made by people, who are irrational and emotional. Even so, deterrence is an extremely important tool in any national security expert’s toolkit, and experts in deterrence are not blind to the importance of world leaders’ perceptions in successful deterrence strategies. However, values analysis can improve deterrence by shedding light on how morals can change perceptions.

Take the loyalty/betrayal value as an example. Here are some quotes that echo the loyalty/betrayal value:

- It is sweet and fitting to die for the homeland. – Horace

- What pity is it that we can die but once to serve our country. – Joseph Addison

- If being personally sanctioned by Russia is the price of standing up for freedom, then I am happy to pay it. America will always stand against tyranny – U.S. Representative Jay Obernolte (R-California)

I’m sure these quotes resonate with readers to some extent, but what else do they have in common? They treat costs (death or sanctions, in these cases) as intrinsically good. Costs, up to and including the ultimate price, are fundamentally morally righteous if they are paid to support your country. And this isn’t a bargain of deterrence. Horace didn’t write, “it’s sweet and fitting to die for your homeland in order to secure greater benefits in the future.” That sentiment deflates the quote, separating it from its moral force. It’s right to die for your country, full stop, not for material benefits that your death would or could bring later generations. Paying costs is proof of your patriotism.

Consequently, when dealing with world leaders who are high in the loyalty/betrayal value, deterrence by retaliation is going to carry a discount; it will be less effective against them, because these leaders would be more willing to pay costs. They want to pay costs. In fact, there may be some additional costs that would raise the likelihood of action (So, you don’t think I’ll pay X for my country? I’ll show you!) This insight has limits, of course. The loyalty/betrayal value is not infinite. But considering millions of people have happily paid the ultimate price in questionable wars in the past, we can conclude that it has a powerful influence on people’s decision-making.

In contrast, deterrence by denial doesn’t suffer from this moral complication. It’s about increasing the risk of failure. No statues were ever built for world leaders who blundered for their country or stoically withstood the consequences of their own mismanagement. In fact, the loyalty/betrayal value may magnify the impact of deterrence by denial. Suffering for your country may be heroic, but causing your country to fail is the opposite. It brings a type of shame that will most strongly be felt by people high in the loyalty/betrayal value.

Deterrence in the current conflict is more circumscribed, as war has already broken out. However, deterrence can be employed to ensure that conditions don’t worsen, perhaps with the use of nuclear/chemical weapons or attacks weapons shipments leaving NATO-held territories. Given that Vladimir Putin is high in the loyalty/betrayal value, resources should first be devoted to deterrence by denial strategies, such as increasing force limits in the region or diversifying supply lines from NATO territory to Ukraine. Certainly, both deterrence by denial and by punishment should be explored, but we should be clear that one is likely to have a greater influence on his psyche than the other.

Conclusion

These are only three of the many insights that Putin’s moral compass reveals. I will end this article here as it is already too long, but I think this exercise has demonstrated how values analysis can be applied to international affairs. I would note that I remain somewhat uncomfortable with this methodology, as I am not certain that Putin’s moral portrait is truly accurate based solely on publicly available materials. However, I remain convinced that this is an avenue of analysis that is worth exploring in the future.